These biographies were originally written for a brochure to accompany a National Trust exhibition.

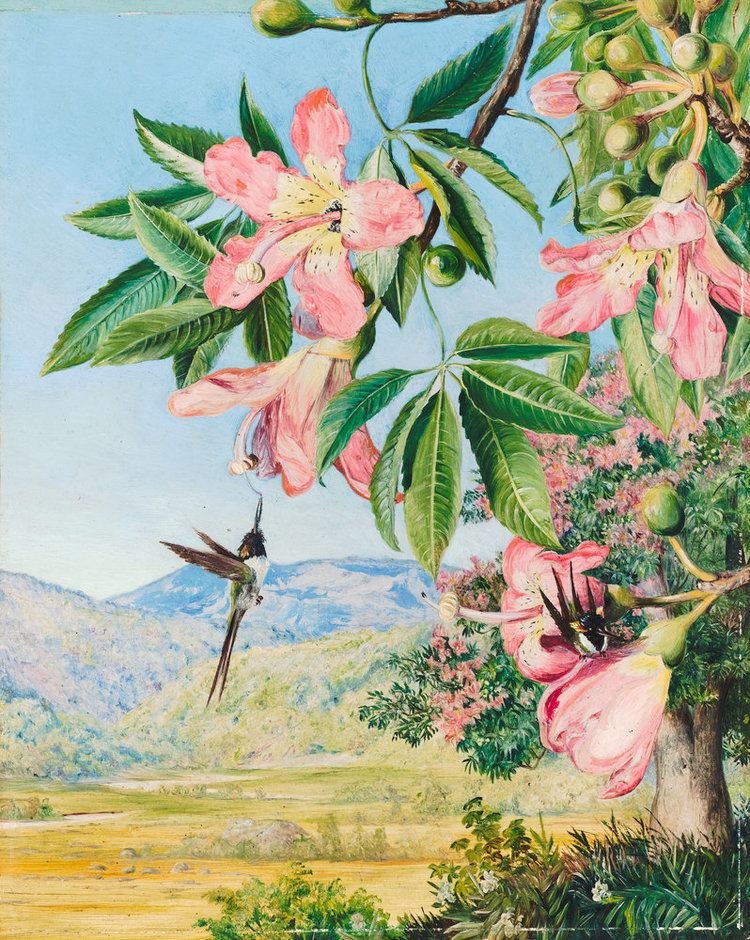

Image: Marianne North ‘A Bornean Crinum’

Mary Delany (1700 – 1788)

Born into a wealthy background, Mary Delany was closely connected with the arts from an early age. It was in later life that art was to play an important role. After the death of her first husband, Delany was embraced by the Duchess of Portland, who introduced her to the world of botany. She was particularly inspired upon viewing the exotic drawings of Josephs Banks, created during a voyage with Captain Cook.

A contented second marriage allowed Delany to indulge her love of gardening, resulting in ‘a surge of activity in a variety of media, all of which the basic theme was the flower.’ Upon becoming a widow for the second time, at the age of 72 she channelled her grief into her most well known artworks, her self-named ‘paper mosaicks.’

These botanically accurate creations were assembled from hundreds of pieces of coloured tissue paper, delicately cut to represent petals, stems and leaves, glued onto a black hand-coloured background. Annotations were both formal and informal. It was said that viewers were unable to distinguish her art from real life specimens. Delany declared,

“I have invented a new way of imitating flowers.”

She created nearly 1000 works in ten years, before her eyesight failed. Ten albums were bequeathed to the British Museum, with two works on permanent display in the Enlightenment Gallery.

Maria Sybilla Merian (1647-1717)

Maria Sybilla Merian was born in Frankfurt to a successful publishing family. Her love of insects began at the age of thirteen, when she began rearing caterpillars, documenting their metmorphosis.

Although she had little formal education, she was born into an era focussing on the documentation of art and science, from both formal and informal perspectives. This allowed Merian to fulfil her desire to explore tropical climes in person, having seen specimens brought back to Amsterdam from the East and West Indies.

In 1699, at the age of 52 and accompanied by her daughter Dorothea, Merian travelled to the Dutch colony of Surinam, South America. Here she embarked upon an entirely new way of documenting the natural world. Unlike her contemporaries who were bringing specimens back to Europe to be painted in studios, Merian carefully observed and painted insects in their natural environment, recording their behaviour in detail; some of these creatures were unknown to the western world.

One of Blickling’s most prized treasures, ‘Dissertations sur la generation et les transformations des inscetes de Surinam,’ by Maria Sybill Merian was created as a vellum volume, and donated by renowned bibliophile Sir Richard Ellys in the early 1740s, was just decades after her expedition.

Her artwork carefully detailed plants that had never been described before; it was so detailed in fact, that Linnaeus used many of her drawings for his classifications. Her early training from Dutch flower painters contributed to her lively, bright watercolour palette,

‘Readers marvelled at the artistry of the plates and relished the view they provided into this bright, mysterious country.’

Sixty engraved plates demonstrate the life cycles of butterflies, moths, insects, plants and animals, with added commentaries on diet and habitat.

Upon returning to Amsterdam, Merian trained her daughters to recreate the engravings, approaching patrons to fund copies of her book. Merian died in 1717, leaving a legacy of an entirely unique oeuvre that remains a marvel to this day.

Marianne North (1830 – 1890)

Marianne North came from a privileged and well-connected background. In her early twenties, she received artistic training from Dutch flower painters, but it wasn’t until a trip to Kew Gardens at the age of 26 that she became determined to see tropical blooms in person.

After the death of her beloved father, at the age of 40 she began a series of worldwide solo trips that would see her visit fifteen countries in just fourteen years. Not only was her travelling style unconventional for the era, but her approach to botanical painting was entirely unique. Gone were the stiff, diagrammatic watercolours of her contemporaries, to be replaced with a limited palette of lively oil colours, injecting life and personality into her subjects. Her sister summarised,

‘Her feeling for plants in their beautiful personality was more like that which we all have for human friends.’

This was achieved not only by painting in natural habitats and recording native uses, but also as a result of North’s dedication to teaching herself about botany through diverse scientific literature and discussion.

Her first expedition to the USA and Canada piqued her interest in conservation and agriculture. Further trips were to follow, to Jamaica, Brazil, Tenerife and Japan. She visited various British colonial territories, such as Singapore. In Borneo, her hostess described her as ‘extremely energetic and rather exhausting,’

Further exploration of Asia (Java, Sri Lanka and India) was followed by a visit to Australasia. Her sister described,

‘The restless mood would come, some obscure corner of the Tropics had to be painted, and once again we heard that she was gone.’

Her penultimate trip was to South Africa, where she completed 110 paintings; 1865 saw a final expedition to the Seychelles and Chile.

Failing health put a stop to North’s travelling, and she returned to England where she wrote her autobiography, dying in 1890.

Perhaps North’s greatest legacy is her gallery at Kew, opened in 1882. Over 800 of her paintings are still on display here, continuing to ensure that those who could not afford the privilege of travel are able to experience the wonders of the world through her art.

Sources:

Molly Peacock ,‘The Paper Garden’ (London: Bloomsbury, 2011)

Kim Todd, ‘Chrysalis: Maria Sybill Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis’ (London: Tauris & Co, 2007)

Michelle Payne, ‘Marianne North: A Very Intrepid Painter’ (Richmond, Surrey: Kew Publishing, 2016)

Leave a comment